How the Phase Changes of Water Affect Cooking

When you apply heat to room temperature water, it gets warmer. This makes sense, and is generally what people expect to happen. When water reaches the boiling point, things get more complicated. This is because water undergoes a phase change from liquid to gaseous. A similar transition occurs when frozen water melts to a liquid. Having a basic understanding of what goes on here can help your cooking in several ways.

What happens?

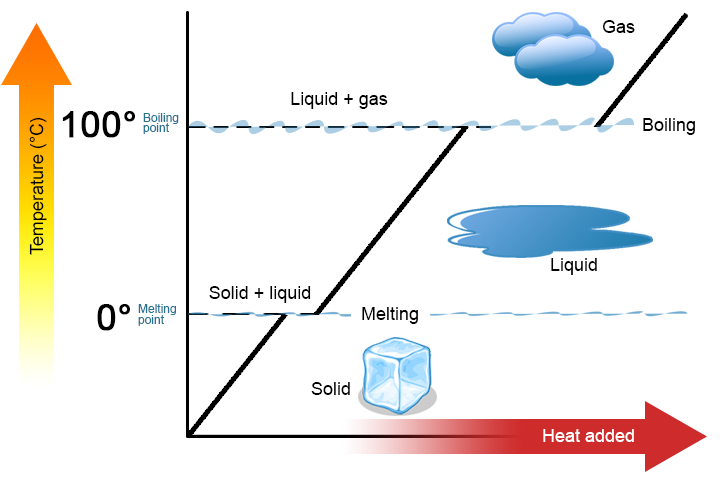

Once a pot of water on the stovetop reaches its boiling point, bits of the water in the pot obtain enough energy to enter the gaseous phase, which causes them to bubble up out of the water. This is what happens when water boils. The energy being applied is used to transition water from liquid to a gas. It does not heat up the water! This corresponds to the flat spots in the graph above.

Water can only exist as a liquid between 32F and 212F (0C and 100C) (To be precise, this is true for pure water at atmospheric pressure, but that’s generally more or less what we’re working with in the kitchen). You can have a container of 212 degree liquid water, apply a bunch of heat to it, and end up with 212 degree water vapor.

You usually don’t need a rolling boil.

Once you bring a pot of water to the boiling point, any actual boiling is a waste of heat, unless your goal is to get the water to evaporate (such as reducing a stock). A rolling boil is useful as a way to see that you have for sure hit the boiling point, but beyond that, it serves no purpose.

If you’re boiling something like pasta, rice, or vegetables, you’re using the water to heat up the food, and to be absorbed by the food. Many people crank the stove up to high, thinking that a vigorous boil speeds this process along. In actuality, all that speeds up is the evaporation of the water in the pot. You only need to add enough heat to compensate for the heat lost to the environment. You can probably leave it as low as it goes. “Simmering” is essentially this - you keep it right at the boiling point, but just barely.

I’ll take that a step further. There’s nothing special about 212 degree water that 211 degree water doesn’t have too, or even 200 degree water! That is, your food will cook almost as quickly in 200 degree water as it does in vigorously boiling 212 degree water. This means you can boil the water, add your food, bring it back to a boil (the food will drop the temperature), then cut off the heat. The pot will slowly cool, but I bet if you checked it 10 minutes later, it’d still be pretty hot. If you’re cooking for a while, you can periodically bring it back up to a boil. Leaving the burner on simmer is probably the simplest approach. Keeping it on high is just a waste of gas.

Browning

Have you ever been frustrated by putting your food in a hot pan, having it sizzle like mad, but not get any appreciable browning? One trick to getting food to brown properly is to make sure that it’s dry. Many people suggest patting off meat with paper towels, and Peking duck is hung to dry before it’s cooked. This is because the phase change of water prevents your food from browning!

Browning and crust formation typically occurs at relatively high temperatures - Wikipedia says a minimum of 280 - 330F (140 - 165C). That is, your food must be at or above those temperatures for it to occur. If whatever you’re cooking is wet, or if it’s sitting in a puddle of liquid, that liquid might be blocking your food from touching the pan, and (unlike oil), it will not get above 212F, so you’ll just end up boiling and steaming your food.

If you pull a steak out of a marinade and throw it in a hot pan, the crust won’t begin to form until the exterior water is gone, at which point, you might be already near the end of the cooking process. Adding liquid to the pan causes the same issue.

This is also why stirring frequently can inhibit browning. Most food contains some moisture. If you put it in a hot pan, the moisture on the surface touching the pan will slowly boil off, then browning can begin. If you stir before this has a chance to happen, then the moisture never fully evaporates, and you never get any browning.

Ice

Have you ever used whiskey stones or those stainless steel ice cubes? They never seem to keep your drinks as cold as normal ice. This is because of the same bit of science - when ice melts, it goes through a phase change, which requires an enormous amount of energy.

Your freezer and everything in it are generally around 0F (-18C). If you put 0 degree steel balls into a 20 degree drink, that drink will warm up the cubes until they’ve equalized. More steel per drink means that this final temperature will be lower (the heat capacity of the material plays in here, but mass is the most important factor). Pretty simple.

This happens much the same with ice, but once that ice reaches 32F, something changes - it can’t get any warmer until it’s been converted into a liquid. At that point, all the heat from the drink goes into the phase transition until the ice is completely melted. This action gives water a huge cooling advantage over materials which don’t undergo a phase transition around that temperature range. The only downside, of course, is that you get water in your drink.